Following the conclusion of COP 28, a pivotal moment has arrived for policymakers, governments, and stakeholders worldwide as they gear up to translate the vital resolutions into tangible actions. In African countries particularly where the impacts of climate change are deeply felt, these recommendations have complex implications. This article explores some of the key recommendations of the COP 28 conference, exploring some of the challenges African governments face in implementing and the necessary conditions for successful implementation and outcomes in favour of the climate transition.

The Conference of Parties (COP) is the apex decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It convenes annually to assess global efforts towards the advancement of the Paris Agreement’s aim of limiting global warming to as close as possible to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, in addition to creating strategies to cut greenhouse gas emissions and ameliorating the impacts of climate change on developing countries. The first COP meeting was held in Berlin, Germany in March 1995, while the most recent meeting (COP 28) was held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, from the 30th of November until the 12th of December 2023.

COP 28 concluded with key agreements, four of which this article focuses on. These are;

- The landmark acknowledgement of fossil fuel as the root cause of climate change,

- A US$700 million pledge to the Loss and Damage Fund,

- A pledge to triple renewable energy by 2030 and;

- The establishment of the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter (OGDC).

- Fossil fuel is acknowledged as the root cause of climate change.

Notably, COP 28 was the first of the conferences to officially acknowledge fossil fuel as the root cause of climate change, heralding the gradual end of the fossil fuel era globally. This acknowledgement was further reinforced with an agreement by the countries in attendance to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science”. Although this development signifies a huge win for Africa, being the continent on the frontline of climate change and the most vulnerable to its multiple devastating effects, its implementation comes at a great cost for the continent.

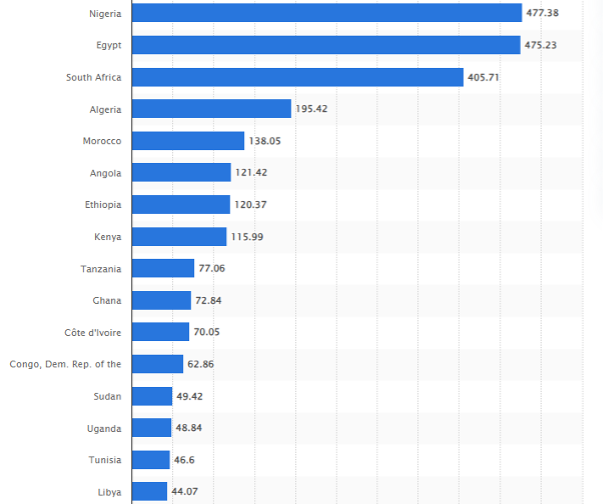

Firstly, African leading economies substantially depend on fossil fuel exportation for revenue generation. Figure 1 shows the countries with the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the continent, and according to data, crude oil is a mainstay for most of these countries. Nigeria, for example, derives 60% of government revenue and 90% of foreign exchange earnings from fossil fuel exportation. It contributes to Algeria’s GDP by roughly 19%. In addition, Egypt holds 4.4 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, produces 682,904.14 barrels per day of oil and ranks 27th in the world. At the same time, South Africa records roughly $1.46B in crude petroleum exportation, making it the 36th largest exporter of crude petroleum in the world. Crude petroleum was the 15th most exported product in South Africa as of 2021.

Figure 1: African countries with the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Source: Statista

Hence, fossil fuel phase-out might cause significant harm to the African economy at large, despite being the key to tackling the most pressing problem that the continent faces at the moment. In his interview with TheCable on COP28 outcome, Saliru Dahiru, the director-general of the National Climate Change Council stated the Nigerian government’s position on fossil fuel phase-out. According to him, “Nigeria will not stop the use of fossil fuels because it is critical to our economy and other developed countries are expanding on their fossil fuel use”. He added that net zero does not require that fossil fuels should be phased out entirely in the continent but that emissions should be balanced with removals, and with adequate support, Nigeria and Africa can maintain their emissions rate at 4% while working towards cleaning the emissions. As a leading oil producer and the largest crude oil exporter in the continent, the position of Nigeria on this subject matter cannot be ignored. African governments need to be adequately represented at the negotiation table and heard before final commitments are made on the phase-out of fossil fuels. In addition, fossil fuel economies in developing countries need to prioritise diversifying their economies to reduce reliance on oil and gas sectors while actively supporting clean and renewable energy infrastructure.

- US$700 million was pledged to the Loss and Damage Fund

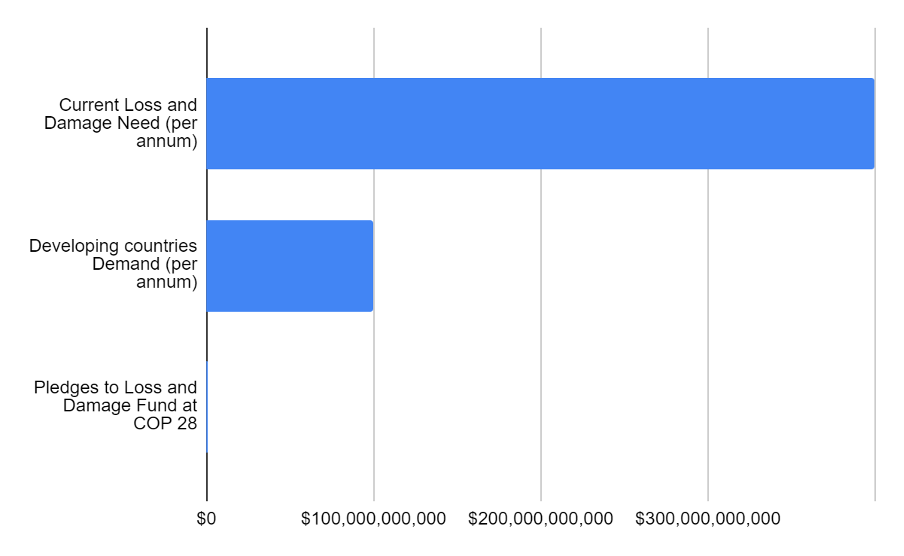

Again, a sum of US$700 million was pledged to the Loss and Damage Fund at COP 28. This Fund was created at COP27 in 2022 to provide fast, accessible, non-debt finance to the growing number of victims of major climate change-related disasters from developing countries. In 2022, only US$230 million was pledged at COP27, while US$700 million was pledged at COP 28. However, when compared with the US$100 billion that is demanded by developing countries and the US$400 billion that is needed yearly, it is only a drop in the ocean. Showing that much still needs to be done in this regard. Figure 2 compares the pledges in COP 28 and the amounts needed each year.

Figure 2: Scale of Loss and Damage needs vs Developing countries’ demands vs Pledges at COP 28

Source: lossanddamagecollaboration.org

This huge deficit shows that exclusively relying on the Loss and Damage Fund and other DFI funds might be unsustainable in alleviating the escalating impacts of climate change on the continent. Hence, it is pertinent that other sustainable means of generating climate finance within the continent are considered. An example of this could be a climate finance tax on the oil and gas companies that operate on the continent. Rough estimates show that at least 500 oil companies operate in the African oil and gas sector. Being one of the major contributors to climate change, a climate finance tax could serve both as a means to deter their activities and raise funds to mitigate the impact of their activities on the continent. In addition, African governments should allocate funds for climate finance in their official annual budgets. This will create a stable source of funding, in addition to enhancing proper planning for climate change mitigation and adaptation across countries in the continent.

- A pledge to triple renewable energy by 2030 was signed by 118 countries

In addition to the Loss and Damage pledges, 118 countries signed a pledge to triple renewable energy capacity and double the global rate of energy efficiency by 2030. The endorsement of this pledge appears to be significantly influenced by a similar pledge that was made at the G20 Summit which was held a few months before the COP 28, where G20 Member States agreed to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030. This underscores the influence of G20 Member States in driving the global net-zero goal, and as a regional bloc member of the G20, Africa has the potential to influence these commitments. However, successfully implementing this pledge in Africa is heavily dependent on public-private partnerships. The private sector has proven itself to be the driver of innovations for major societal change as displayed in the roles it played in combating the recent Covid-19 pandemic. With appropriate incentives in the form of favourable regulations, tax credits, grants, and feed-in tariffs, it can drive the actualization of this pledge by 2030 in Africa. For example, South Africa’s renewable energy market has recorded significant growth. It reached 13.21 gigawatts (GW) in 2023, and it is estimated at 16.58 gigawatts in 2024, and 28 gigawatts by 2029, as a result of its new energy legislation, favourable power purchase agreements and its renewable energy independent power producer procurement programme. Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Morocco, and Mauritania have integrated renewable energy targets into their national energy plans and aim to achieve 100%, 62%, 60%, 52%, and 50% renewable energy by 2030 respectively. This is achievable with a strong public-private partnership.

- Finally, An oil and gas decarbonisation charter was signed by 50 oil companies

Over 50 national and international oil companies, representing about 40% of global production, signed a decarbonisation charter; the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter (OGDC). This global industry Charter aims to accelerate climate action in the industry. The initiative sets three main aims;

- To achieve net zero emissions in each company’s direct operations (as opposed to the use of their products) by or before 2050;

- To achieve near-zero methane leakage from the production of oil and gas by 2030, and;

- To achieve zero routine flaring (burning excess gas) by 2030.

Due to the rich deposits of oil in the continent, many national and international oil companies operate in Africa, thereby accounting for roughly 8% of the global oil output as of 2022. Rough estimates show that at least 500 oil companies operate in the African upstream oil and gas and some of these oil companies including Shell, ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies and National Oil Companies including Nigeria’s NNPC were signatories to the COP28 oil and gas decarbonisation charter. However, achieving the aims of this charter would require significant investment in innovative technologies in decarbonizing the sector demanding strategic policy support and investment in clean technologies.

In conclusion, the aftermath of COP 28 unfolds a critical juncture for global climate action, particularly in the context of African countries where the impacts of climate change are deeply embedded in their socioeconomic fabric. In navigating the complex landscape of climate action, it is imperative that African nations actively participate in shaping global discourse, ensuring their unique challenges and circumstances are duly considered. COP 28 catalyzes collaborative efforts, urging governments, stakeholders, and the private sector to work collaboratively towards sustainability in Africa.

About the Author(s)

Olayide Oyeleke is an associate at The AR Initiative; where Dr Emma Etim is the Head of Research.