The aggravating environmental impacts of single-use plastic items and styrofoams recently led to the ban of their usage and distribution in Lagos State, Nigeria. Despite the potential benefits that this new development offers, it presents certain complexities and controversies which might hinder a successful implementation. This article explores these complexities, underscoring the need for a nuanced and balanced approach, which takes into account environmental concerns, economic considerations, and the practicality of alternatives. =

Historical background to single plastics and styrofoam usage

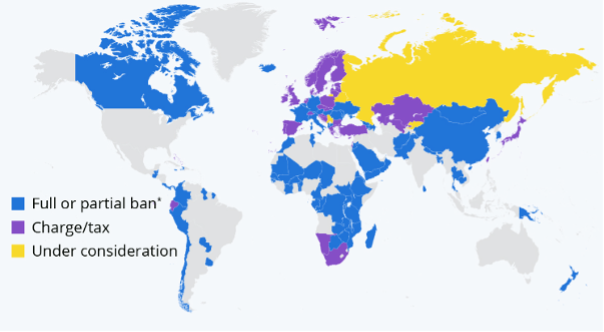

The history of single-use plastics and styrofoam dates back to the early 20th century, while global adoption occurred between the 1980s-1990s. This widespread adoption was significantly fueled by many factors, including the convenient and portable packaging solution that they offer for fast-food items, cost efficiency, durability, and the allowance for easy customization and branding which creates a consistent and recognizable image for businesses. In addition, consumers became accustomed to the convenience they offer over time, and in response to their demand, the usage became the norm. However, the late 20th century witnessed increasing environmental awareness, leading to concerns about plastic pollution as the durability of plastics meant that they accumulated in landfills and polluted oceans, thereby contributing to GHG emissions through anaerobic decomposition which produces methane, incineration or degradation of microplastic under sunlight. This concern resulted in the enactment of certain legislation to either restrict the use of single-use plastic items through taxes or impose an outright ban on their usage and distribution. The first of such bans was introduced by the government of Bangladesh in 2002, and according to a UN report, roughly 154 countries have adopted some form of legislation to either regulate specific single-use plastic items like bags, spoons, and straws or completely ban all single-use plastic items, with varying degrees of enforcement. (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The Countries Banning Plastic Bags

Source: Statista

The controversies

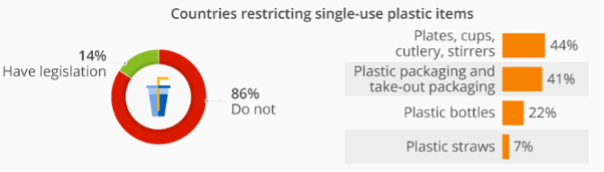

Globally, the implementation of these bans or restrictions is complex and controversial due to a myriad of reasons. First, the plastic industry is a significant contributor to many economies globally. Banning its products can have economic repercussions, affecting businesses, jobs, and entire industries. For example, the plastics industry is one of the largest manufacturing industries in the United States. It generates roughly $451 billion per year in shipments and employs about 993,000 people directly and more than 1.5 million indirectly. In addition, plastics are indispensable in certain applications, especially in the medical sector where single-use tubes, syringes, catheters, lancets, bandages, gloves and more are recommended for health purposes. Also, enforcing a plastic ban requires effective governance, infrastructure, and monitoring systems, which governments may struggle to enforce and regulate, leading to scepticism about their effectiveness. Hence, despite the obvious environmental impacts, these controversies have resulted in a global slow-paced movement towards single-use plastics ban, and according to a U.N. report, only 14% of countries in the world have been able to ban or restrict single-use plastic items. (See Figure 1)

Figure 2: Countries restricting single-use plastic items

Source: Statista

What next?

Tackling this complexity and controversy in Lagos state particularly requires a comprehensive and context-specific approach, which could involve phased implementation of bans or restrictions, coupled with awareness campaigns, infrastructure development, and support for sustainable alternatives. This demands a robust collaboration between governments, businesses, and communities. An example of such collaboration is the implementation of the Single-Use Plastic Bag Law 2015 in England. This law empowered businesses to charge a 5 Pence tax, later 10 Pence on single-use plastic carrier bags. The result of this collaboration with retailers was a 98% fall in the use of single-use plastic bags in the country over a period of 7 years, as the annual distribution of plastic carrier bags by seven leading grocery chains in England plummeted from 7.6bn in 2014 to 133m in 2022.

In addition, actively engaging the grassroots through partnerships with community leaders and grassroots awareness campaigns is central to the successful implementation of the single-use plastic ban. This is because changing habits and behaviours related to single-use plastics requires a bottom-up approach, and grassroots campaigns are effective in influencing individuals and communities to adopt sustainable practices, encouraging them to reduce, reuse, and recycle.

Can this ‘No’ to plastic be a ‘Yes’ to paper and cotton?

Evidence from previous plastic item restrictions also shows that consumers tend to switch to alternatives that have larger carbon footprints causing bigger environmental harm. For example, common alternatives to single-use plastic bags include cotton bags and paper bags, whereas, research by the Northern Ireland Assembly found that it “takes more than four times as much energy to manufacture a paper bag as it does to manufacture a plastic bag.”. This is in addition to deforestation that results from tree harvesting and the use of noxious chemicals for the production of paper bags. Also, the production of cotton bags has the highest carbon footprint. A study by the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark found that an organic cotton tote needs to be used at least 20,000 times to offset its overall impact on production. That equates to daily use for 54 years — for just one bag.

Way forward

Therefore, the need to invest in research and development aimed at finding sustainable alternatives for single-use plastic and styrofoam, as well as providing funding support for startups that are aiming to figure out a lasting solution to the challenges of single-use plastics and styrofoam. For example, with biopactic material, a Kenyan-based Chemolex is creating a recyclable, reusable and 100% biodegradable food and product packaging material to completely replace the use of single-use plastic polymers. The biopactic material is bio-based material that is produced from invasive water hyacinth plants that grow aggressively in Lake Victoria in Kenya. In addition, Rwandan-based Toto Safi has also created an alternative to single-use plastic-based diapers with sustainable cloth.

In conclusion, the successful implementation of single-use plastics and styrofoam bans and restrictions demands a robust approach that balances concerns on the environment, economy and practicality of alternatives. It becomes important, therefore, that the government collaborate with private sector organizations in the creation of context-specific sustainable alternatives, while adopting a bottom-up approach for effective behavioural change at the grassroots.

About the Author(s)

Olayide Oyeleke is an associate at The AR Initiative; where Dr Emma Etim is the Head of Research.