Recent developments surrounding the acceptance of Tuvalu climate change migrants by Australia necessitates a conversation on the legal gap in the protection of climate change displaced people. Despite the increasing climate extremes experiences and the consequent spike in records of climate-induced displacements, the legal ground for the issuance of refugee status according to the 1951 and 1967 Refugee Convention remains limited to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion in the applicant’s country of origin. In addition, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has no legal definition for “climate refugee”. The implication of this defect could be devastating for extremely vulnerable populations that might be forced to evacuate their regions and cross international borders due to the partial or complete obliteration of their countries, as it infers that they are not entitled to the same level of legal protection of human rights as refugees or citizens. Hence a need to accelerate conversations on the legal protection of people who are forcibly displaced by climate change.

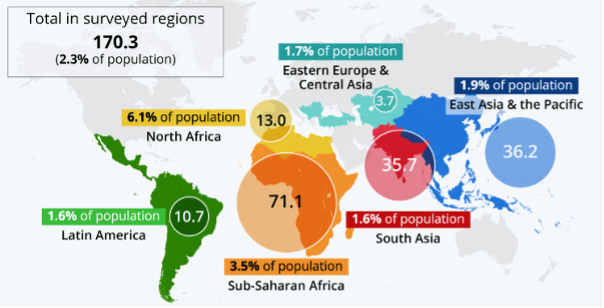

Globally, millions of people have been displaced on account of climate extremes such as tropical cyclones, torrential rainfall, heatwaves, and droughts, with billions predicted to be displaced in the coming years (see Figure 1). In South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, about 21 million people have been displaced by storms and floods according to Statista, while rising temperatures in many countries of Sub-Saharan Africa dependent on rainfed agriculture and coastal erosion in West Africa are leading to internal migration.

Figure: Average number of internal climate migrants by 2050 per region (in millions)

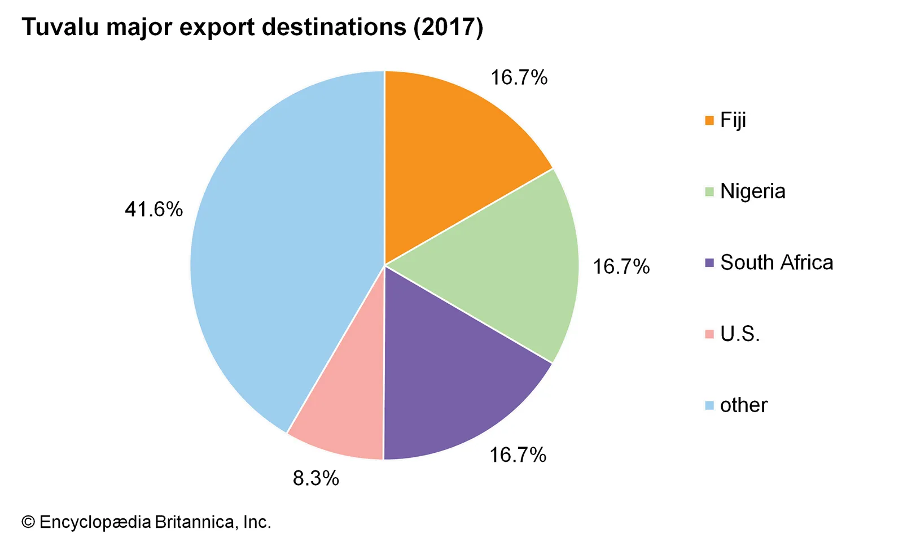

The consequence of these incidents is multifaceted. It poses a great burden on the international community as affected populations reportedly face multiple challenges that include human rights violations, discrimination, economic hardship, an increase in the risk of health issues due to inadequate living conditions, struggle to access basic services such as healthcare, education, and sanitation; thereby threatening global efforts to actualize the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. In addition, it disrupts international trade, supply chains and the global economy. For example, Tuvalu is a top exporting country. Its top exports are tug boats ($108M), non-fillet frozen fish ($19.3M), nitrile compounds ($157k), integrated circuits ($111k), and electrical power accessories ($86.6k), with exporting partners spanning the African continent, the USA, and the Philippines (see figure 2). Its forceful displacement by climate change would lead to supply chain disruption for its exporting partners and interference with global trade.

Figure 2: Tuvalu’s major export destinations

Most importantly, the absence of legal protection for people who are displaced by climate change makes the situation more devastating. In March 2018, the UN Human Rights Council declared that climate refugees do not fit the definition of “refugees” and called them “the world’s forgotten victims.” The implication of this is that people displaced by climate change across international borders are not afforded the same level of legal protection for their human rights as refugees or citizens. Hence, they face threats like deportation and multiple human rights violations including the right to liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to social protection, to an adequate standard of living and to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental well-being, for some, their right to life. A United Nations report shows that more than 50,000 lost their lives during migratory movements between 2014 and 2022. Furthermore, women and children who make up the majority of this population account for worse treatments. In addition to other human rights violations, the women experience gender-based violence while children are subjected to starvation and malnutrition.

Although few processes including the Cancun Adaptation Framework which was the first significant recognition of the issue of climate change-induced displacement and migration under the UNFCCC, the Warsaw International Mechanism, the Global Forum on Migration and Development, the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants and Nansen Initiative’s Agenda have been undertaken at both international and regional levels to wholly or partly address displacement related to climate change, none has explicitly addressed the legal protection of the rights of the displaced. The most expansive exploration of the rights of climate-displaced people is found in the Nansen Initiative’s Agenda for the Protection of Cross-Border Displaced People in the Context of Disasters and Climate Change which identifies coordination on human rights as one of the key elements for future action, but portrays another significant weakness. According to the Nansen Initiative’s Agenda:

“People who have moved across international borders in disaster contexts are protected by human rights law, and where applicable, refugee law. However, international law does not address critical issues such as admission, access to basic services during temporary or permanent stay, and conditions for return. While a small number of states have national laws or bilateral or (sub-)regional agreements that specifically address the admission or temporary stay of foreigners displaced by disasters, the vast majority of countries lack any normative framework.”

This legal gap calls for urgent attention, especially because the number of climate change-displaced people from vulnerable communities is predicted to significantly increase in the coming years. As the world prepares for COP 28 and other climate change events, it is important to accelerate conversations on the legal protection of vulnerable populations whose homes have become unsafe and inhabitable as a result of climate change extremes. Where efforts to mitigate or adapt in situ are inadequate to avert the risks faced by these communities, planned migration that promises adequate legal protection of their dignity and human rights should be the next line of action.