The first world Startup Act was passed by Italy in 2012 – with the mission to spur innovation demand and foster entrepreneurship in the country. The strong impact of this Act on Italy’s startup ecosystem and economy motivated African countries to follow suit, with Tunisia leading the movement in 2018. Unlike other laws that emanate from government representatives or members of parliament, the Tunisian Startup Act adopted a participatory approach that accommodated opinions of actors within the startup ecosystem – entrepreneurs, investors, civil societies, legislatures etc. Members of the ecosystem pushed and accompanied the process from the initial brainstorming phase, through the design of the measures, the discussion and voting in the legislative bodies to the implementation of the law. Senegal followed suit in 2019, becoming the second African country to enact a startup Act. In addition to Tunisia’s framework, Senegal introduced three tax-free operational years for startups, training for youth and female entrepreneurs, and a startup registration platform easily accessible on a government website. The successful passage of Startup Acts in Tunisia and Senegal launched multiple proposals in other African countries that desire to create an enabling environment for startups and investors. Thus, Nigeria and Congo signed their startup bills into law in 2022, with more countries – Rwanda, Ghana, Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda in the pipeline.

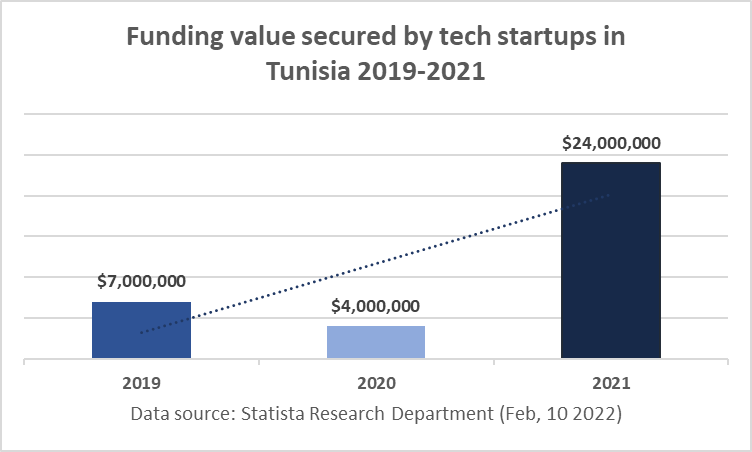

Albeit indirect, a causal relationship exists between an enabling Startup Act and economic growth – because while the Act creates a more friendly environment for startups to thrive, startups in turn generate more revenue for the economy. For example, data shows a significant increase in funding secured by tech startups after the Act was enacted in Tunisia – specifically between 2019 and 2021 (see chart below).

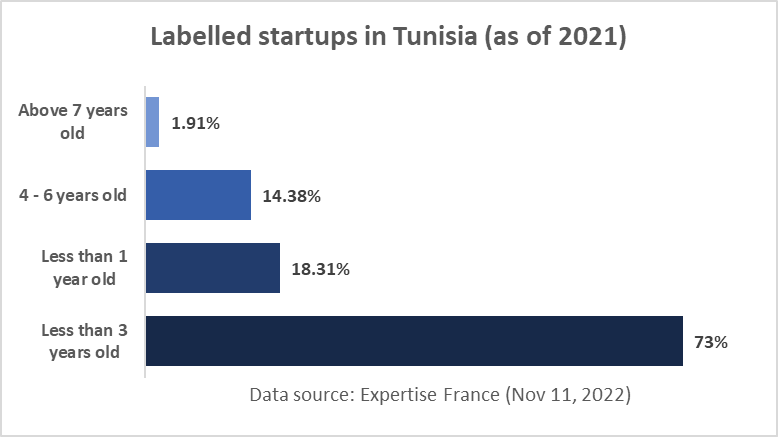

The drop in funding secured by Tunisia tech startups in 2020 was a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, according to a report by Expertise France, 73% of labelled startups in Tunisia as of 2021 were founded after the enactment of the Act (see chart below). The Tunisian Startup Act certainly increased the incentives for young people to start a venture, investors, to put their money into promising companies, and other ecosystem actors to lend their support where it’s needed.

Before the Nigerian Startup Act was enacted in October 2022, data revealed that the tech sector was already outperforming the giant oil and gas sector in revenue generation. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the ICT sector contributed to Nigeria’s GDP by 16.20% in Q1 2022 and 18.44% in Q2 2022, while the contribution of the oil sector, which used to dominate the country’s GDP bottom line was 6.63% in Q1 2022 and 6.33% in Q2 2022. With the newly enacted Startup Act in the country, we anticipate a domino effect of regulatory changes across different government entities, effectively enabling a broader strategy to position the country as an innovation hub by leveraging an emerging tech scene to improve economic development.

Adopting an ecosystem-centred approach

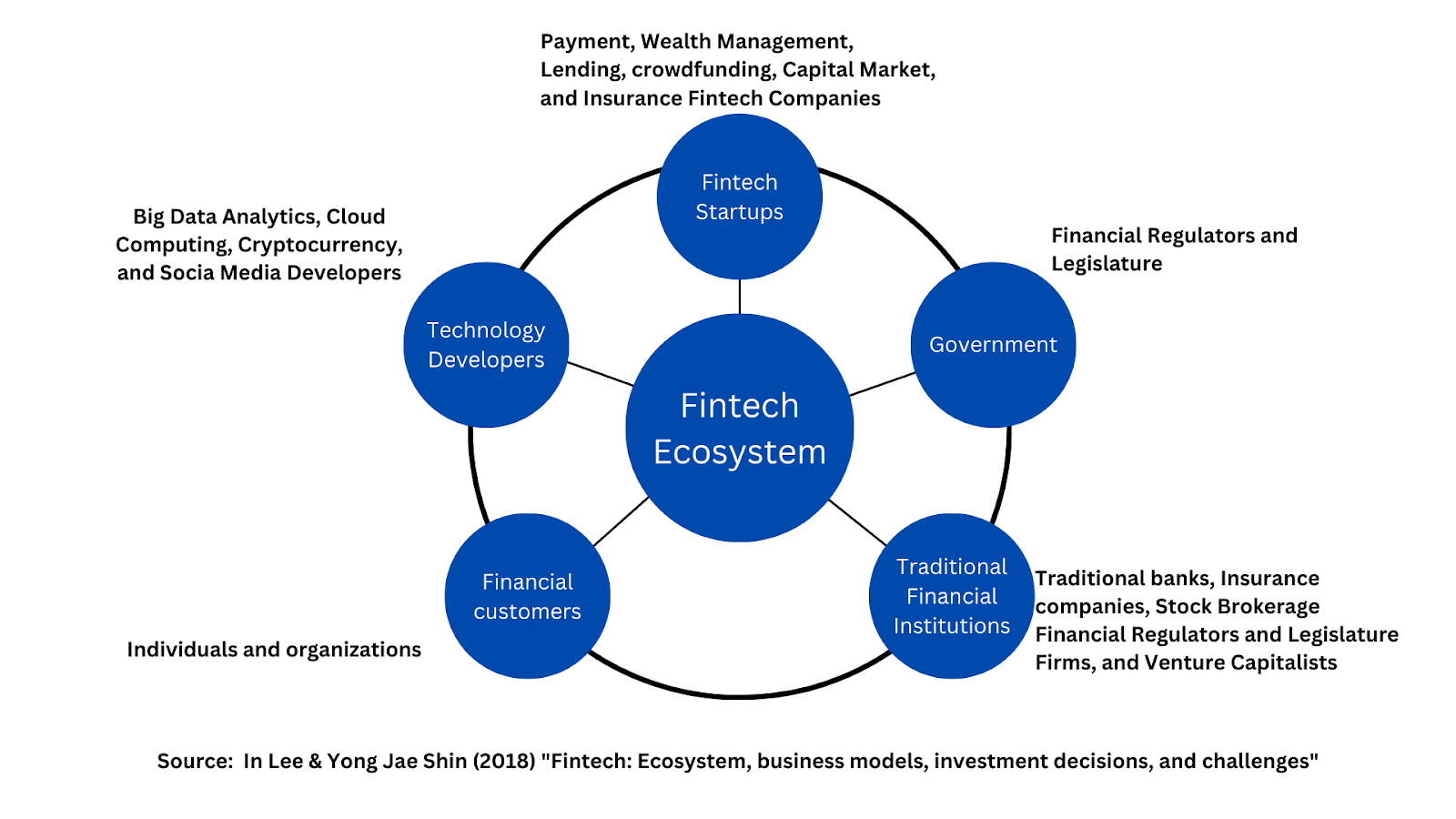

Startups do not exist in isolation – they coexist and depend on other actors in the ecosystem. The term ‘ecosystem’ was introduced into the entrepreneurship policy analysis specifically because the interaction between the components in the ecosystem is critical to understanding the challenges that may impede entrepreneurship and potential solutions. See a fintech ecosystem in the chart below.

Creating startup laws to foster entrepreneurship and innovation without a long-term, holistic, and well-coordinated plan that protects the startup ecosystem is futile. For example, if a policy increases access to finance but entrepreneurial skills to develop a business are lacking, the financing might be difficult to disburse and financiers might complain about the lack of pipeline. It is therefore fundamental to adopt an ecosystem approach recognising the interdependence of multiple factors and the fact that policy measures could have positive or negative consequences on the business environment as a whole.

The enactment of the Act alone will not produce long-term results without thorough monitoring and evaluation. A benchmarking study of African Startup Acts by i4policy in 2020 showed a critical gap in systematic results tracking and evaluation – in fact, specific monitoring and evaluation clauses were not provided in most of the Acts. Though the Nigerian Startup Act established a National Council for Digital Innovation and Entrepreneurship, with the power to appoint a council agent that oversees and makes reports on monitoring and implementation of the Act – this Act failed to provide a succinct monitoring and evaluation clause. The importance of monitoring and evaluation is well established – thus, we encourage a review of the old African Startup Acts for the addition of clear-cut routine monitoring and evaluation clauses, and the establishment of a dedicated executing body in the Act, we also admonish that the Startup Acts in the pipeline should follow suit.

Key Recommendations

The proven benefits of the Act to the growth of startups in Africa, and economic development enhanced its adoption in Tunisia, Senegal, Nigeria and Congo with more African countries in the pipeline. However, startups exist in an ecosystem – hence, it is futile to simply enact the Act without a long term, holistic, and well-coordinated approach that factors in the startup ecosystem, as well as clear-cut monitoring and evaluation clauses.

We encourage African countries that do not have a Startup Act, especially the ones with the largest populations, largest diaspora talent networks and largest growing youth populations in the continent to enact their Startup Act. Furthermore, we admonish countries that are currently creating their Startup Act to use an ecosystem participatory methodology in the process; adopt a holistic, long term, well-coordinated approach; and also provide a detailed monitoring and evaluation clause in the Act. Finally, We recommend that Tunisia, Senegal, Nigeria and Congo should review their Acts to provide detailed monitoring and evaluation clauses and a dedicated execution team in the Act.

About the Author(s)

Olayide Oyeleke is an associate at The AR Initiative; where Dr Emma Etim is the Head of Research.